Final Paper - Information Studies 260 - Description and Access Professor G. Leazer, DLS

“LGBTQ” Cataloging for Inclusion or Exclusion?

An Exploratory Analysis of Banned Book Lists and Catalog Tagging Practices Impact

Introduction

“To avoid controversy, some libraries choose their own classification numbers to avoid shelving children’s and fiction materials in nonfiction sections. Include materials in areas designated for the genre and audiences of the same age.”

“Identifying books with a GLBT label may prevent library users from accessing them for fear of being outed.”

American Library Association Report, GLBT Rainbow Round Table Sections on Cataloging and Labeling

The American Library Association’s Round Table group provides the above guidance in their open access toolkit for library professionals to use in order to better serve GLBT students and other users. In thinking about the ways in which systemic and other forms of bias appear in our cataloging and labeling systems, I was immediately interested in thinking about the ways in which LGBTQ themes may or may not be challenged in children’s and young adult library settings. For me, this a personally relevant issue, and just after I came out myself, I remember that there emerged a culture war debate over the book And Tango Makes Three by Peter Parnell and Justin Richardson. This book is a true story about two male penguins who are given an abandoned egg to raise which appeared in the top most challenged books eight times according to the American Library Association’s Office of Intellectual Freedom Banned Book Week reader (Gomez, 2022). I began to think about the problems of access, cataloging and description of books for younger audiences and the ways in which queer themes are accurately represented. I will begin with a brief literature review where I will look at the theory behind the benefits and challenges associated with naming and not naming LGBTQ content in children and young adult literature. I will then provide a short explanation of my methods and modes of inquiry and then proceed to test two hypotheses: first, that books tagged as LGBTQ will appear more frequently in the ALA Ban List than non-LGBTQ tagged titles and second, books appearing on the LGBTQ Top Ten Reading List will appear on the ban list. I will end with addressing possible alternatives to address the issue of cataloging and description in this setting going forward.

Literature Review

“Deep in the human unconscious is a pervasive need for a logical universe that makes sense. But the real universe is always one step beyond logic.”

― Frank Herbert, Dune

I began my exploration of this topic by first doing a general search for various organizations with reading lists or bibliographies associated with young person’s literature featuring LGBTQ content. I quickly discovered the ALA GLBT Round Table and the information provided there, and I followed several of those resources to their source material (“Rainbow Round Table”). I also started with Mr. Lee Wind’s website that focuses on curating lists of different kinds of LGBTQ literature, with topics ranging from gay and lesbian main characters to gender queer parents/caretakers and many things in between (“Leewind.com”, I’m Here. I’m Queer, What the hell do I read?). Several major themes appeared throughout the existing research on this topic including ideas of censorship, representation and the important role of institutions and institutional support. I conducted a review of the literature that relates to banned books, LGBTQ representation and description/access in information professions more broadly.

Description, Access, and Information Professions

Michael Gorman, in Our Enduring Values, presents an historical and philosophical perspective on the various thought traditions in knowledge organization systems and the library (Gorman, 2015). Ultimately, he arrives at the conclusions that there are certain principles which can be derived from multiple traditions, namely; stewardship, service, intellectual freedom, rationalism, literacy and learning, equity of access and privacy (Gorman, 35-36). Each of these, in his estimation, form a kind of meta-responsibility to library professionals throughout the history of the library in the modern world. Melodie Fox and Austin Reece pick up a similar thread of inquiry in their analysis of the library and information professions through the lenses of utilitarianism, deontology (Kantism), justice ethics (John Rawls), ethics of care (feminist praxis), Derrida, and John Dewey’s pragmatic approach(Fox and Reece, 2012). In the end, Fox and Reece seem to appreciate Dewey’s pragmatism foremost among these various theories but incorporate all of them in their recommended model. They propose that we, as ethical professionals, should center a duty to care, be hospitable with mitigation, be consequence driven with an emphasis on improvement, treat people with basic rights and responsibilities, and not continue to take actions which we know to be wrong (Fox and Reece, p. 381-382). I believe that grounding any understanding of the state of current library practice is assisted by knowing and understanding these competing influences and schools of thought internal to the professional community. I also believe that this allows us to better understand the ways in which libraries as institutions of social and cultural meaning interact with different publics and users.

Kay Mathiesen proposes with a conceptual framework that challenges librarians to achieve informational justice in the library (Mathiesen, 2015). In a similar vein, Emily Drabinski uses a queer theory perspective to challenge basic principles and ideas of categorization that all information professionals and institutions engage in in order to catalog and provide access to their collections (Drabinksi, 2013). Drabinski proposes that there is in effect, no way for corrections to fully keep up with changes in knowledge and knowledge systems, instead they propose that there must be a reciprocal relationship, whereby, librarians assume a responsibility to engage users of the library in practices that will allow them to ultimately find and conduct searches in a way which is holistic and meaningful to their ends (p.94). Mathiesen codifies this perspective, among their four key principles of informational justice, by stating, “while all four strategies are worthwhile, it can be said that the third - treating people justly as seekers, sources, and subjects of information - is the core of what it means to be socially just” (p.206-207). These perspectives focused on justice, challenge the ethical frameworks provided earlier and complicate our understanding of the role of information professionals, and how the systems we use can be thought of/used to either reinforce or oppose systems of inequity in society.

LGBTQ Themes and Description

Among the literature focused on LGBTQ themes in children’s and young adult books, there clearly emerged overlapping interest and concern relating to censorship and access. It appears that there are several competing philosophies that are ascendant. Librarians want to ensure their collections contain works that are representative of the whole range of human experiences but should this be accomplished by segregating non-normative expressions in books and other media, should content be included among other like works but identified as LGBTQ, or if they should not be identified as LGBT and simply normalized through being only identified by the other major themes/categories to which the work may belong is still an unsettled question. Aligned against these possible modes of inclusion are calls to ban this content all together. Brianna Burke and Kristina Greenfield address the problems with a lack of representation along this axis by articulating that students, “absorb heteronormative values, and of LGBTQ students, that they seldom see themselves or their struggles reflected” (Burke and Greenfield, 2016). They go on to cite a National Council of Teachers of English study which found that 64% of LGBTQ students felt unsafe in the classroom and at school (P.47).

Curwood et al. identify a key failing of many primary education institutions, which often have missions that focus on multiculturalism and diversity but they often do not consider queer identity to be included in that mission (Curwood et al, 2016). They also highlight the effect that disproportionate banning’s of LGBTQ themed literature has on academic environments and individuals who may want to include them, specifically, self-censorship (p.41). Due to a number of factors like lack of institutional support, fear of backlash from students/parents, and lack of personal expertise in the area many teachers simply opt to not engage with these materials at all. The effects of this are clear, LGBTQ students are excluded from learning environments and non-LGBTQ students are less exposed to experiences different than their own. Ultimately, preventing them from developing critical thinking and culturally sensitive knowledge. Jill Hermann-Wilmarth quotes a National School Climate Survey which finds that 33% of students were harassed in their schools due to their actual or perceived sexual identity (2007). The lack of representation of LGBTQ themes in the curricula of primary schools has real world consequences that are far reaching. Thinking back to the ideals presented by the various theorists in the previous section, it would seem that libraries, and educators in general, in primary schools are failing to meet their ideals for the LGBTQ communities they serve.

Methods and Hypothesis

“I could be chasing an untamed ornithoid without cause”

LCDR Data, Season 4, Episode 11

I originally set out to do a short quantitative analysis of previously published materials looking at and comparing the following: (1) number of YA and Children’s book published each year, (2) Number of Challenges logged each year by the American Library Association, (3) What percentage of those challenges were against books tagged as LGBTQ (4) What percentage of those books had LGBTQ themes but were not tagged (5) How many of the books appearing on the annual LGBTQ ALA top 10 reading list appeared on the banned list that year.

My preliminary finding is that there is a huge gap in publicly available data relating to the fields of children’s and YA literature publishing. It was relatively easy to find financial statistics like sales, volume of books sold, ebook downloads etc, however, there is almost no publicly available information about raw publication data. I also had significant trouble in finding a database which had already tagged all of the relevant titles, that is to say, I did not find one.

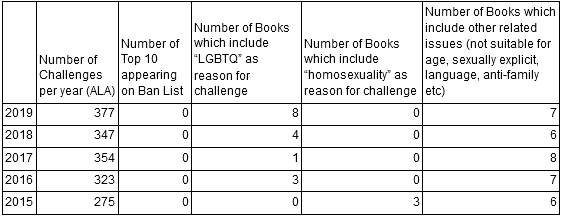

Appendix A and B Contain information drawn from the ALA site, which offers curated data which I have included here for reference and which includes a list developed from combining information from the Ban List and the Top Ten recommendations from each of the last 5 years.

Hypothesis

H1: Books tagged as LGBTQ will appear more frequently in the ALA Ban List than non-LGBTQ tagged titles.

H2: Books appearing on the LGBTQ Top Ten Reading List will appear on the ban list.

Findings

While looking at the lists of books which are identified by the two groups at the ALA I was somewhat surprised by my findings. None of the books which appeared on the top ten reading list for the ALA LGBTQ group appeared on any of the ban/challenged lists in the year which they were recommended. As a result I must reject my secondary hypothesis.

My primary hypothesis was somewhat more complicated. Based on the stated reasons for the books being challenged, almost none for explicitly for “homosexuality.” However, a significant number were challenged for “LGBTQIA+ Themes” including a majority of those books challenged in 2019. If we expand our analysis to include non-normative experiences or coded language which often substitutes for not wanting to appear anti-LGBTQ with phrases like anti-family, sexually explicit, or unsuitable for age then we find that more than three quarters of all challenged books include those themes. However, this is not a perfect metric for determining if a book is actually tagged as being LGBTQ in the systems to which they belong, for this reason, I also must reject my primary hypothesis due to lack of information. I would note however that LGBTQ themes do seem to be greatly over represented one could imagine a situation in which books about war, violence, or crime that appear in literature that is available to young adult readers make up a lion's share of the books challenged instead of LGBTQ themes. I would like to propose that a more nuanced, thorough and funded assessment of this field might uncover other trends and factors which are not available based on the constraints of this particular project.

Conclusion

“Time moves in one direction, memory another. We are that strange species that constructs artifacts intended to counter the natural flow of forgetting.”

-William Gibson, Distrust That Particular Flavor

As the ALA quotes at the opening of this paper identified there is a need for ensuring accessibility while also ensuring that the users of libraries are able to gain that access safely and effectively. Information professionals hold a set of responsibilities and ideologies that influence the ways in which we interact with our communities, provide services and access, and shape young people's world view more broadly. As I discussed above, these ideologies sometimes take the form of ethical inquiry or philosophical disposition, but at the end of the day, there is a practical need which we seek to fill to the benefit of our organizations and in conjunction with the communities in which we reside. When considering our practice in dealing with sensitive issues like sexuality and gender identity there is a heightened need to ensure that we are both working to fulfill our ideological goals in terms of justice and access, and we must also be sure to do so in a way which honors the experience of the people who use our systems. While my conclusions here showed that my hypotheses were rejected I do believe that there is still a significant area for exploration. I would propose that until we reach a point where students are not harassed in schools at the rates described above because of their perceived sexuality, that we need to continue to focus on exposure and education. In that mode, I believe that continuing to highlight content as LGBTQ is a necessary action. We know today that descriptive representation makes a difference in the lives of young people and our literature and knowledge systems should reflect that.

Bibliography

Burke, Brianna, and Kristina Greenfield. "Challenging Heteronormativity: Raising LGBTQ Awareness in a High School English Language Arts Classroom." The English Journal 105, no. 6 (July 2016), 46-51.

Curwood, Jen S., Megan Schliesman, and Kathleen T. Horning. "Fight for Your Right: Censorship, Selection, and LGBTQ Literature." The English Journal 98, no. 4 (March 2009), 37-43.

Drabinski, Emily. "Queering the Catalog: Queer Theory and the Politics of Correction." The Library Quarterly 83, no. 2 (2013), 94-111. doi:10.1086/669547.

Fox, Melodie J., and Austin Reece. "Which Ethics? Whose Morality?: An Analysis of Ethical Standards for Information Organization." KNOWLEDGE ORGANIZATION 39, no. 5 (2012), 377-383. doi:10.5771/0943-7444-2012-5-377.

Gomez, Betsy. "Banned Spotlight: And Tango Makes Three." Banned Books Week | September 27 – October 3, 2020. Accessed December 12, 2020. https://bannedbooksweek.org/banned-spotlight-and-tango-makes-three/

Gorman, Michael. Our Enduring Values Revisited: Librarianship in an Ever-Changing World. Chicago: American Library Association, 2015.

Hermann-Wilmarth, Jill M. "Full Inclusion: Understanding the Role of Gay and Lesbian Texts and Films in Teacher Education Classrooms." Language Arts 84, no. 4 (March 2007), 347-356.

"Infographics." Advocacy, Legislation & Issues. Last modified July 30, 2019. https://www.ala.org/advocacy/bbooks/frequentlychallengedbooks/statistics.

Mathiesen, Kay. "Informational Justice: A Conceptual Framework for Social Justice in Library and Information Services." Library Trends 64, no. 2 (2015), 198-225. doi:10.1353/lib.2015.0044.

"Rainbow Round Table (RRT)." Round Tables. Last modified February 6, 2020. https://www.ala.org/rt/rrt.

Wind, Lee. "Lee Wind, Author of "Queer As a Five-Dollar Bill"." I'm Here. I'm Queer. What the Hell Do I Read?. Last modified July 3, 2018. https://www.leewind.org/2018/07/lee-wind-author-of-queer-as-five-dollar.html.

Midterm Paper - Information Studies 260 - Description and Access Professor G. Leazer, DLS

Representing Documentation

Using Fanon to read the Documentalist Movement

The documentalist movement led by Paul Otlet identified the need for a systemization of record keeping as the rate and volume of knowledge production expanded at the turn of the 20th century. His work with Henri LaFontaine at the International Institute of Bibliography and its subsequent iterations the Universal Bibliographic Repertory (RBU), International Office of Bibliography (OIB) and their utilization of the Universal Decimal Classification (UDC) form the basis of this critique (Rayward 1994, p. 238-40). This idea was presented by Otlet as a utopian desire to collect the world's knowledge and catalog it for posterity, in effect producing a universal encyclopedia of all human knowledge. When understood in the context of the time and place of Otlet and viewed through critical lens we can instead understand this project as one of a colonial empire seeking to extend its colonial holdings into the sphere of knowledge and information studies.

We know that naming and naming conventions matter and in the field of information studies we need only look to the use of the preface of the Oxford libraries 1674 catalog as evidence that seemingly concise and focused technical applications for these conventions can be used much more broadly than originally intended. As in the case of The Bodleian and Sir Thomas Hyde who’s naming conventions went on to be used by the whole of English colonial empire as written for more than 200 years (Pettee 1936, p. 276). So when Otlet introduces words like universal to his particular brand of forming a system of code to catalog, describe and access the world's knowledge it seems to immediately evoke the opposite. The linguist Mary Louise Pratt describes this phenomenon in Shock and Awe: War on Words where she describes how the word security seems to evoke the opposite as a function of it generally being used only in times where it is not present or the subject needs to be addressed and you should be afraid as she lays out, “It’s effective because you’re not not talking about fear, you're assuming its there - or should be” ( 2004, p. 140). In the case of Otlet, the term universal seems to immediately circle us back to the idea that this is in fact not a universal system or repository of knowledge, but rather, the singular mission of a small group of European hegemons seeking to expand their knowledge of the world, read as other, in the hopes of centering the worlds knowing in the cradle of colonial Europe. In effect, while observing the impending collapse of the old world order following the events of the first world war Otlet’s actions are actually a new form of colonial control manifest.

In his revolutionary work Wretched of the Earth (1961) Frantz Fanon describes the various mechanisms and realities of life in a colonial state. In his discussion of national culture he describes the situation in definitive terms, “to fight for national culture first of all means fighting for the liberation of the nation, the tangible matrix from which culture can grow” (1961, p. 168). At first glance this description may seem tangential to the matter at hand, the collection of ideas and knowledge by Otlet, however, Fanon goes on to expand his frame, arguing that, “National culture is the collective thought process of a people to describe, justify, and extol the actions whereby they have joined forces” (1961). The first mode of knowing that a national culture is free in his estimation centers around the idea of a decolonial people to be able to describe an independent collective thought process. Fanon would in this framing likely see Otlet’s desire to catalog the world's knowledge as a continuation of the oppressive colonial regimes which national culture must be formulated against and as he expresses earlier in his same text that nothing comes from the colonizers for free and any emergence from under the colonial rule is hard won through the fight of the occupied nation (Fanon 1961, p. 92). Even in cases where some national autonomy is won, he is skeptical of its use as the formerly colonized people cling to the structures created (of which a system of knowledge organization and record keeping would be one) that are not “placed at the service of the people” (1961, p.68). A system of knowledge based in Brussels and collected by Europeans would likely not be seen as accessible to a post colonial Africa as it continues to center the white European colonial settler nations at the expense of the rest of the world.

In order to understand the effect of this process Fanon again can provide a helpful lens, especially when considered alongside the work of Suzanne Briet. If we are to understand the nature of primary and secondary/subsequent documentation being a function of the living breathing original, as per her famous antelope par example, then we can understand humans and human knowledge in the same manner (Briet 1951, p.11). In her example the cataloged antelope is the primary document while the others are derivations of that original. To Fanon this same construction holds true, “A slow construction of myself as a body in a spatial and temporal world” becomes the basis of the body schema, in much the same way as Briet constructed the antelope (Fanon 1952, p. 91). And similar to the antelopes taking on a documentalist meaning once it leaves its habitat so too does Fanon challenge us to consider the colonial implication, “All colonized people...position themselves in relation to the civilizing language” and he goes on defining the Black man relation to the metropole, “the more the colonized has assimilated the cultural values...the more he will have escaped the bush” (Fanon 1952, p 3.). In this sense we can see how the relationship of the antelope to the human world mimics the construction of Fanon where the Black colonized person is perceived relative to the metropole and its whiteness. The violence is also one of dehumanization. If we are to take Otlet at his word and assume utopian intention then we can also use the colonial lens to understand that effort.

Otlet set out to catalog human knowledge using a universalized system which has been seen to be a colonial project at its core. To understand the personal experience of a system like this in a decolonial perspective we can look at documentalism as an ontological endeavour. To which we can see how a Black body may experience this through the words of Fanon, “Ontology does not allow us to understand the being of a black man, since it ignores lived experience” (Fanon 1952, p. 90). Even in the case of an application in the mode of Briet we can see the cataloging of humans, human knowledge and experience in a colonial context as being essentially a dehumanizing one, and as Fanon attests, “it is utopian to try to differentiate one kind of inhuman behaviour from another” (Fanon 1952 p. 67). In this sense, Otlet may actually be able to be considered a utopian, if not exactly in the terms he may have viewed himself. Building on the idea of the body schema Fanon goes on to explain that underneath this layer there is an additional historical-racial one as well, and with this in mind the violence of cataloging in the colonial context is multiplied, as Fanon articulates “I was responsible not only for my body but also for my race and my ancestors” (Fanon 1952, p. 92). Through this lens then we can see the damage of Otlet’s colonial project as amplifying the preexisting history of violence perpetrated against Black bodies in a colonial setting.

The central focus of Otlet’s ideas seems at first glance to be a sound endeavour, one that likely leads to the advance of numerous technological and social-cultural devices that improve the field of information studies. Rayward draws a throughline from the turn of the 20th century work of Otlet to emergence of the internet which is in no small part likely to be a defining characteristic beginning of the 21st in the least, and more likely beyond even that. However, this somewhat rose colored lens approach to Otlet’s work masks the history of colonial rule that the preceding centuries were rooted in. It completely ellides the contributions of decolonial movements in challenging the systemic oppression of the period. It reinforces instead the hegemonic authority of colonial powers and likely formed the basis for the now endemic forms of technologic/cyber racism embedded in our information systems environment highlighted by the work Safiya Noble among others. As systems and methods become more invisible and more ubiquitous it is incumbent upon us more than ever to critique and assess the real world application, theoretical frameworks, and cultural impact of these systems in the evolution of the human experience. If we are committed as a species to ideas of justice and equity, if as a community of knowledge we are seeking truth then we must do as Caliban did, and use the tools of the master to break down the house.

Bibliography

Briet, S., Day, R. E., Martinet, L., & Anghelescu, H. G. B. (2006). What is Documentation?: English Translation of the Classic French Text: Scarecrow Press.

Fanon, F. (1952). Black Skin, White Masks (R. Philcox, Trans. Revised ed.). New York: Grove Press.

Fanon, F. (1961). The Wretched of the Earth (R. Philcox, Trans.). New York: Grove Press.

Fussey, P. (2015). Command, control and contestation: negotiating security at the London 2012 Olympics. The Geographical Journal, 181(3), 212-223. doi:10.1111/geoj.12058

Pettee, J. (1936). The Development of Authorship Entry and the Formulation of Authorship Rules as Found in the Anglo-American Code. The Library Quarterly: Information, Community, Policy, 6(3), 270-290. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/4302278

Pratt, M. L. (2004). Security. In J. A. G. Bregje van Eekelen, Bettina Stötzer, Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing (Ed.), Shock and Awe: War on Words

(Vol. 1, pp. 185). University of California, Santa Cruz: North Atlantic Books.

Rayward, W. B. (1994). Visions of Xanadu: Paul Otlet (1868-1944) and hypertext. Journal of the American Society for Information Science, 45(4), 235-250.